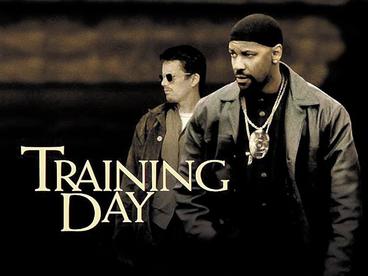

Training Day premiered during my sophomore year at Orrville High School. Mashing up Denzel Washington and Ethan Hawke in a police drama struck the right chord with this budding pubescent demographic. Action, purpose, the kid from White Fang and everyone's favorite actor from Pulp Fiction coalesced in ways that enticed our teenage sensibilities. Of course, the content - the violence, the language, the drugs, the concepts of grey areas in justice - were all beyond us as an audience, but like Hawke's character, we became apprentices to a caricatured version of LA. Preaching is Training Day every Sunday for the church. Instead of an overemphasized version of Orange County's flaws, however, we're trained in the otherworldly language of the church. Two of my church history professors, Warren Smith and Sujin Pak, spoke of the importance of learning the language of our faith. For Dr. Smith, the language of the early Christian fathers and mothers held great importance because those words, found especially in creeds, revealed the agreed upon theological foundations of the faith. For Dr. Pak, the language of the Reformation showed us how Christians wrestled withe tradition while meeting the unforeseen realities of a brave new world. In both instances, the language they used, which still forms the ways we think about God, faith, church, mission, discipleship, and creation, still matters. In one sense, preaching should train us with the language of our forebears. In quite another, though, preaching trains us in the language of scripture, and especially the scriptures that don't fit nicely on bumper stickers and memes. Sermons properly arise from a preacher's personal wrestling with the Bible, and that struggle ought to compel the congregation into their own engagement with God in God's written word. Some might here argue that we should use a single translation of the Bible so we can have a singular memory of certain verses. After all, do we walk through the valley of the shadow of death or the darkest valley in Psalm 23? However, that's not at all what I believe is important about learning biblical language. Rather, learning the content of the Bible gives us the language to make sense of the world in which we live. However you translate Psalm 23, we hear a promise of a God who walks with us through times of anxiety, fear, and tragedy. We hear of a God who feeds and feasts us even in the face of enemies. That language, in whatever variations, now give us powerful words to speak to church communities facing tragedies like our recent natural disasters of hurricanes, wildfires, and earthquakes in the Northern and Western Hemisphere. While the movie sensationalized the violence of city life, preaching should train congregations in honesty. Honesty about the challenges we face and the triumphs we experience. Honesty about the sins that plague us and the forgiveness that saves us. Honesty about the difficulty of living God's justice in our world and the resolute commitment that God has for justice anyway. This is honesty about God, about us, about creation, about all things. Even as preaching trains us in holy language, it should not train us in sterile language. We should remember that words like "shit" appear in the Bible (Phillipians 3:8). Rather, preaching should train us in honest language. Words of lament and righteous anger should appear in the pulpit alongside words of thanksgiving and hope. Preaching is ultimately the comingling of the language of God's Kingdom with today's vernacular speech. Too much Kingdom language and all we'll hear is a foreign tongue. Too much familiar language and there's nothing that sets a sermon apart. Perhaps most importantly, like Denzel in Training Day, preachers are complicated characters. While we're proclaiming the Gospel of grace and exhorting God's people to saintly life, we stand before these people as sinners. We're held to a higher standard and yet know our own faults too deeply, too intimately. We're enacting God's grace before the eyes of God's people: sinners made saints leading congregations full of sinners made saints. Any preaching that doesn't acknowledge the fallibility of the preacher isn't Christian preaching. Any preaching that elevates the preacher to a pedestal breaks the second commandment (idolatry) and obscures the ultimate content of the sermon: God's very self. We're not to point to ourselves. We're to point through ourselves to the God about whom we speak, in whom we live and move and have our being, for whom we preach. If you're coming to church, then, don't just look for a "good message." Look to be trained. Give the sermon your close attention and listen for how God is calling you to shape your life as a disciple of Jesus.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSimultaneously a sinner and a saint. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed